Yves Klein ââåthe Evolution of Art Towards the Immaterial

Yves Klein: The man who invented a colour

The Frenchman was an artist, showman and inventor – who created a hue that had never existed before. How did he achieve this? Alastair Sooke reports.

One summer's day in 1947, three young men were sitting on a embankment in Nice in the southward of France. To laissez passer the fourth dimension, they decided to play a game and split upwards the world between them. One chose the creature kingdom, another the province of plants.

The tertiary human being opted for the mineral realm, earlier lying back and staring upwardly at the ultramarine infinity of the heavens. Then, with the contentment of someone who had suddenly decided what course his life should take, he turned to his friends and appear, "The blue sky is my showtime artwork."

That homo was Yves Klein, whom the New Yorker's art critic Peter Schjeldahl described in 2010 equally "the concluding French artist of major international event". In a menstruation of prodigious creativity lasting from 1954 to his death from a tertiary heart assail at the historic period of 34 in 1962, Klein altered the class of Western fine art.

He did so thanks to his commitment to the spiritually uplifting power of color: gilded, rose, merely higher up all, blue. In fact, his chromatic devotion was then profound that in 1960 he patented a color of his own invention, which he called International Klein Blueish.

Razzle dazzle

Born in 1928 with 2 painters for parents, Klein always displayed a penchant for showmanship. He loved magic also as the cabalistic rituals of the mystical Rosicrucian society, and the influence of both would afterward manifest itself in his work.

After spending a year and a half in the early 1950s mastering judo in Japan, where he earned a black belt, he eventually settled in Paris and devoted himself to art. His outset exhibition of monochrome paintings in various colours was held in the private showrooms of a Parisian publishing house in 1955.

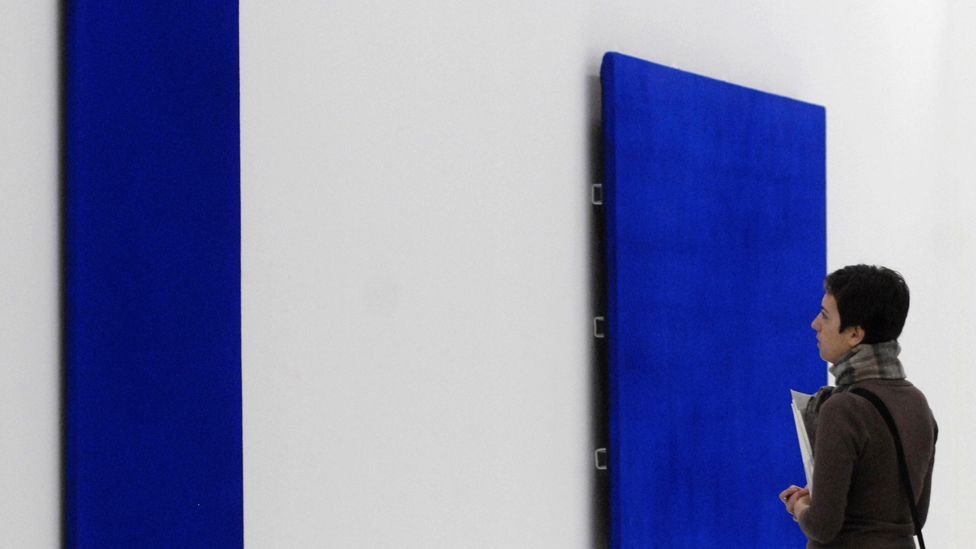

Yves Klein paintings on brandish equally role of Blue Revolution exhibition at the Mumok Museum in Vienna in 2007 (Samuel Kubani/AFP/Getty Images)

His short career was characterised by many radical gestures, often touched with his flair for spectacle. To gloat the opening of a solo exhibition in 1957, for instance, he released 1,001 helium-filled blue balloons in the St-Germain-des-Prés district of Paris. The following twelvemonth, an exhibition now known as 'The Void' consisted of cipher more than than an empty gallery – yet it attracted a crowd of 2,500 people that had to be dispersed by police.

Leap Into the Void, his famous black-and-white photo of 1960, presents Klein soaring upwardly from the parapet of a building like a Left Bank Superman. Like all feats of magic, though, the photograph is actually a play a joke on: in this case a montage, then that the tarpaulin held by some friends, which would take softened Klein's landing, has disappeared.

Perhaps his near notorious performance, though, occurred in March 1960, at the opening of his Anthropometries of the Blueish Epoch exhibition in Paris. On this occasion, footage of which can exist viewed online, Klein appeared earlier an audition wearing a formal tailcoat and white bowtie. While nine musicians played his Monotone-Silence Symphony (a single annotation fatigued out for 20 minutes, followed by a farther 20 minutes of tranquillity), Klein directed iii naked models as they covered themselves with pasty blue paint, earlier imprinting images of their bodies upon a white canvas. The models had become, he said, "living brushes".

Klein photographed in front end of 1 of his Blueish Sponge Sculptures in the tardily 1950s (Express Newspapers/Getty Images)

"The genius of Klein is becoming more than and more apparent," says Catherine Forest, Tate Modern'south curator of contemporary fine art and performance. "He has been dismissed past some art historians as a adventurer or – because of his use of naked female models – as conventional and sexist, but his strategies were playfully critical and are condign more significant in their influence for the younger generation. It could exist argued that he was a critical prankster on par with Duchamp."

Expanding the spectrum

For all his influence on conceptual fine art, though, Klein was most preoccupied with colour. As early every bit 1956, while on holiday in Nice, he experimented with a polymer folder to preserve the brilliance and powdery texture of raw however unstable ultramarine pigment. He would somewhen patent his formula every bit International Klein Blue (IKB) in 1960.

Before that, though, he made his proper noun with an exhibition held in Milan in Jan 1957 that included 11 of his unframed, identical signature blue monochromes, one of which was bought by the Italian artist Lucio Fontana. This show ushered in what Klein called his "Blue Revolution", and soon he was slapping IKB onto all sorts of objects, such as sponges, globes and busts of Venus. Even his 'living brushes' dipped their flesh in IKB.

Art historians still debate the significance of Klein's use of ultramarine. For some, it represented a break with malaise-ridden brainchild, which was popular in the wake of Globe War II. Painted mechanically using a roller, Klein's flat, blank monochromes seemed to rebuff expressionist art.

Klein's Blue Sponge Sculptures (Thomas Lohnes/AFP/Getty Images)

For other scholars, though, Klein'south depthless monochromes and obsession with 'the void' can be understood as expressions of the threat of nuclear holocaust. "We absolutely must realise – and this is no exaggeration – that we are living in the atomic age," Klein one time said, "where all physical matter tin vanish from one day to the next to give up its identify to what we tin envision as the most abstract."

Yet perhaps his honey of blue is less specific and more than profound. Klein was a pious Cosmic, and in religious art blue frequently represents eternity and godliness. For example, Giotto, whom Klein admired, was a vivid advocate of bluish. Klein's ultramarine monochromes are not overtly Christian, just he certainly used the sensuousness of IKB to advise spirituality. As he once said, "At first in that location is null, and then there is a profound nothingness, after that a blue profundity."

Certainly, his rich, radiant monochromes share a singular characteristic: they all take a vertiginous quality that seems to suck the states out of reality towards another, immaterial dimension. The effect of looking at them is not dissimilar to meditating upon a deep azure sky – something that Klein perchance intuited as a beau, on that beach in Prissy in 1947.

Klein's 1960 painting Great Blueish Anthropophagy, Homage to Tennessee Williams (Olivier Laban-Mattei/AFP/Getty Images)

When because Klein, so, it is important to remember that for all his stunts and attention-grabbing performances he was a sensualist as much as a provocateur – and that this accounts for his fondness for colour. "For Klein, pure colour offered a way of using art not every bit a means of painting a picture, simply every bit a style of creating a spiritual, almost alchemical experience, beyond time, approaching the immaterial," explains Kerry Brougher, who curated the major retrospective Yves Klein: With the Void, Full Powers at the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC, in 2010.

"Out of all the colours Klein used, ultramarine bluish became the most important. Unlike many other colours, which create opaque blockages, ultramarine shimmers and glows, seemingly opening up to immaterial realms. Klein's bluish monochromes are non paintings just experiences, passageways leading to the void."

Alastair Sooke is art critic of The Daily Telegraph

If y'all would similar to comment on this story or anything else you lot accept seen on BBC Culture, caput over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter .

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20140828-the-man-who-invented-a-colour

0 Response to "Yves Klein ââåthe Evolution of Art Towards the Immaterial"

Post a Comment